Before I get to my post on "as long as they are reading", I have a lot of exciting news this week. First, A Quill Ladder is out. Check it out. If you received a Review Copy, I would love it if you post your review. No pressure (I am not a pressure kind of person), but I would sure appreciate it. Also, check out my new Reader Bonuses section of my site. I have lots of great giveaways happening. Second, Tales From Pennsylvania, an anthology to which I contributed, set in Michael Bunker’s Pennsylvania, will be out November 21, and I have free ARC copies for those who are willing to leave a review. Just sign up for my blog or drop me an email. And last but not least, I am writing a short novel to contribute to the Apocalypse Weird world. Sign up to receive a free ARC of Nick Cole's contribution to the Apocalypse Weird world and other exciting stuff. More news is coming on this soon!

The Percy Jackson Problem

Since I am a writer of middle-grade fiction fantasy, an article regarding “The Percy Jackson Problem” by Rebecca Mead in The New Yorker recently caught my eye. I had thought the article might be about some of the weaknesses in Percy Jackson, and the general darkness and relativism I find in some modern children’s literature of The Hunger Games ilk that I think taken alone, might be providing not quite the moral and hopeful messages that I think children need to hear at least some of the time.

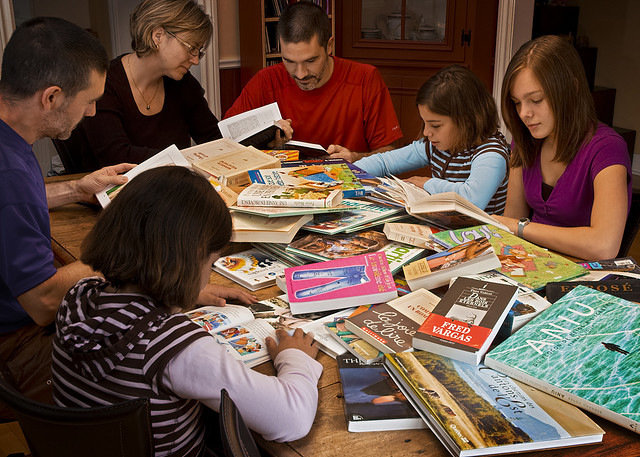

Photo Credit: PIerre Vignau / flckr/ Creative Commons

However I was very wrong as to the nature of the article. It started with Neil Gaiman’s claim that as long as children are reading, that in and of itself is a good thing:

“’I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children,’ [Gaiman] argued, adding that it was ‘snobbery and … foolishness’ to suggest that a certain author or particular genre might be a baleful influence upon young reading minds—be it comic books or the works of R. L. Stine.”

But Apparently It's Not...

Mead proceeded to “debunk” Gaiman's assumption based largely on the arguments contained in an essay by Tim Parks that appeared on the blog of the New York Review of Books. According to Mead,

“Parks argued that there is little evidence to suggest that readers will make progress ‘upward from pulp to Proust.’ ‘I seriously doubt if E.L. James is the first step toward Shakespeare,’ he concluded. ‘Better to start with Romeo and Juliet.’

Hmm, really? Mead then proceeds to unfavorably compare Percy Jackson to Harry Potter for its “slangy, casual style” and notes that:

“Riordan’s books prompt an uneasy interrogation of the premise underlying the ‘so long as they’re reading’ side of the debate—at least among those of us who want to share Neil Gaiman’s optimistic view that all reading is good reading, and yet find ourselves by disposition closer to the Tim Parks end of the spectrum, worried that those books on our children’s shelves that offer easy gratification are crowding out the different pleasures that may be offered by less grabby volumes.”

Basic Assumptions of the Argument

While I do not disagree that from a writing quality perspective, that Harry Potter is probably superior to Percy Jackson, and I agree to some extent a lifetime of never moving beyond Rick Riordan is probably undesirable. However when I delved further into Parks’ original essay, I was troubled by the sentiments it contained for reading and for children’s literature. I have boiled Parks’ essay down into the following primary assumptions.

- There is a stairway of books with E.L. James, Rick Riordan and George R.R. Martin on the bottom and Dostoevsky, Faulkner and Pamuk on the top. I actually had to look Pamuk up—pretty bad for a writer, I know.

- We have this illusion by reading whatever they want people will pass up the ladder from soft porn (Fifty Shades) to Crime and Punishment.

- We WANT them to pass up the ladder, because the books at the top are in fact “better.”

- The evidence simply does not support this passage up the ladder.

- In fact, given that genre fiction is addictive like junk food, one might well fall down the ladder instead of up. Parks observes,

“If anything, genre fiction prevents engagement with literary fiction, rather than vice versa, partly because of the time it occupies, but more subtly because while the latter is of its nature exploratory and potentially unsettling the former encourages the reader to stay in a comfort zone.

Therefore, according to Parks, we should reconsider being happy when we see our teenager immersed in George R. R. Martin instead of watching TV.

Yikes!

Problems with the Argument

A key problem I have with the essay is the thin evidence Parks brings to bear to support argument number 4 above:

- One essay by W.H. Auden in which Auden says that if there is a detective novel around he cannot resist opening it, and if he opens it, he will not get any serious work done until it is finished.

- Parks’ own “powerful experience with this”—a spell reading Simenon’s Maigret novels in which after reading five or six it becomes difficult to distinguish them from each other—therefore it is clear that they stimulate and satisfy “a craving for endless sameness, to the point that the reader can well end up spending all the time he has available for reading with exactly the same fare.”

- His own children have chosen to read crime novels, pulp fiction, and fantasy novels instead of Parks’ favorite (and presumably much more accomplished) writers such as Coetzee, finding the latter too disturbing or real.

- His students seem firmly entrenched in the world of genre fiction and do not see the “essentially conservative nature of the one and the exploratory nature of the other” and do not understand why the authors they read are not in the same category as Doris Lessing or D.H. Lawrence.

(Really the whole essay was a rather stultifying adventure in literary name dropping. I appreciate that Parks appreciates these writers, but one feels there is more at play with all the names than him simply expressing admiration for these writers).

So coming back to Parks’ point, he concludes that it is evident that reading does not form a continuum whereby one is led from the more simple (Fifty Shades) to the more complex (Crime and Punishment) and that genre and literary fiction engage their readers in different ways (probably not an untrue statement), and scratches his head in confusion with regard to why:

“right-thinking intellectuals continue to insist on this idea, even encouraging their children to read anything rather than nothing, as if the very act of reading was itself a virtue”

When did these genre book pushers become right-thinking intellectuals? What does Parks even mean by that? But I digress…

He seems to believe that the thinking that the very act of reading is a virtue is driven by publishing houses that want to feel good about pumping out millions of copies of Fifty Shades of Grey, and intellectuals who want to believe that the hoi polloi can be learned up to appreciate Proust. However Parks concludes that “there are many ways to live a full, responsible, and even wise life that do not pass through reading literary fiction.” Whew! Really? Thank goodness. He just feels that for some reason that nobody wants to accept that reality (Hunh? Most people seem to have accepted that just fine), and observes that those people of his kind, lucky enough to find enrichment in the joys of Shakespeare are just blessed.

While I appreciate Mr. Parks’ dedication to “great” literature, I find his arguments concerning for readers, writers, and appreciators of books everywhere.

Reasons the Argument is Concerning

First, let’s be clear here that I am no fan of Fifty Shades of Grey, Twilight or even, although his work is considerably better, Rick Riordan, but why does Mr. Parks have to center his whole argument around comparing one end of the book continuum to the other? There is a whole host of books that occupy the stairwell in between the two extremes and one might argue that there is more mobility up and down those middle stairs than there is between the top and bottom stair. There is high-quality exploratory genre fiction, and more reader-friendly literary fiction, and there is an entire category in the middle of crossover fiction. While many people may never make their way to the top stair and revel in the joys of Pamuk or Proust, they might dabble in Margaret Atwood and David Mitchell and still enjoy a good Louise Penny along the way.

As two of the commenters on the article more astutely observed:

“Impugning the value of all so-called genre fiction by attacking E. L. James or Stephanie Meyer is analogous to dismissing seafood by pointing out the flaws in canned tuna.”

And

“One problem with the argument presented here is that Parks implies throughout that genre fiction and bad writers of genre fiction are synonymous, while limiting his discussion of serious literature to the greats. That’s like saying classical music is superior to rock n roll because Bach is superior to Nickelback.”

Second, why do we assume that getting to the top stair and reading Faulkner and Coetzee, is or should be the goal of all readers? I am sorry, I find much literary fiction that Parks has listed on the “top stair” to be dense, overly gritty, and boring. I suppose that marks me as a plebe, but I do not think I approach reading as a complete anti-intellectual. I do have a PhD, albeit probably in what some would consider a lesser discipline, and graduated at the top of my class. I even won fellowships and hold a reasonable job as a researcher. I dabble in all sorts of kinds of fiction on many stairs of the ladder. I have tried to appreciate some of the writers that Parks seems determined to foist on all of us and have found it wanting from my perspective for my tastes.

There is a certain accepted style to much of what is considered great literature, and if that style is not to one’s liking, then I guess one is forever condemned to the lower rungs of literature. As one commenter on Parks’ article noted:

“If you want to be one of the literary crowd, you'd better embrace gritty negative realism to the exclusion of all else; if you happen to like a book that has, say, a happy ending, or characters that manage to not cheat on each other or murder their family members, then you're out.”

This seeming obsession of those who claim to love literature with the classics and the narrow confines of deep literary fiction, is in my opinion is one of the worst forms of intellectual snobbery and is a grand disservice to literature and reading. Who has not been at a book event, or hanging with bookish people, only to have at least one of them (the most cultured and learned generally) falling over themselves to list some of the great literature they have read lately, (or at some point in their lives) or discuss the finer points of Melville? There often is no adequate response to their verbal barrage of literary greats, which in my opinion, unless they are obtuse and do not realize most people have no idea what they are talking about, or are just so in downright love with the books that they read, is expressly designed to highlight how well read, how superior, how utterly cultured they are. Or, it is a fear-based response, based on the concern that I may have actually read more and better books than they, and they had better expound on their list first, to make sure I know it.

Gee, that’s great, but I’m reading Gone Girl, and I was thinking of picking up Cloud Atlas, but I might just indulge in a little Percy Jackson with my kids for a bit. Being able to talk passionately about books, and what books one likes, while honestly considering and expounding on their qualities, without fear of being judged, could be one of the first and key steps to seeing some of the flaws of those books and moving up or around on the reading stairway. Nobody is going to do that in the presence of someone who only reads Faulkner.

Reading is not, and should not be, a competition. It should be something we do for pleasure, for intellectual stimulation, for learning, and for a whole range of reasons. To suggest that if one is not reading Proust, one is ensconced at the bottom of the stairwell staring slack-jawed at Fifty Shades of Grey…or shudders, Percy Jackson, is faulty.

Is any reading good reading? Good is a very dangerous term. I would not call reading comics “good” reading, but it is not therefore “bad” reading. It is reading. If kids read comics for pleasure, they are learning the mechanics of reading, and reinforcing the idea that reading is enjoyable. Will some of them then move on to the plebeian joys of Harry Potter? Probably. Will others eventually read Joyce? Also probably. Will some of them never read in favor of reality TV and video games? Again, probably.

My kids barely read. Before you make assumptions regarding the lack of literary guidance in my house, my house literally teams with books, I will buy any book for my children that they request and I read to them so much when they were little that I am pretty sure the handsome librarian thought I had a thing for him. Yes, I prefer that they read something a bit more intellectually stimulating than Captain Underpants, but let me assure you that if they were reading Percy Jackson, I would be over the moon.

There is a real danger of over intellectualizing reading for children at the cost of good plain fun and losing a generation of readers along the way… if indeed we have not already done so. While I do not disagree with trying to steer them to consider a variety of books, and point them generally away from Captain Underpants in favor of gasp the Chronicles of Narnia, or even horrors, Enid Blyton, which Mead confessed was her guilty pleasure as a child, I think most reading is good reading, or decent reading—which is why, bringing me back to one of the original reasons for this blog post, I think you should check out my Derivatives of Displacement series. It is intelligent, fun, and not too dark. But I digress :-).

Moving around up and down the stairway of reading as an adult, and as a child, and understanding the differences between the books on each level, gives one more appreciation of the different styles of literature and the different objectives of different writers. Even Fifty Shades of Grey is an illustrative read of the obvious zeitgeist of the day, and can be consumed, at least partially, with the intellectual desire to understand why it appealed to so many people. Believe me, I have written many blog posts in my head with regard to the dangers of loving Fifty Shades of Grey. I just don’t think Proust and Dostoevsky are the necessary alternatives.

What do you think? If you like my blog, consider subscribing, so you don’t miss out on a single post.